Lines We Didn’t Rehearse

On January 4th of this year, 17-year-old Josiah Wheeler was found dead in his Alaskan wilderness cabin. After almost a week of waiting, grieving family and friends were finally informed that it was carbon monoxide poisoning that had claimed his young life. Josiah and Charity’s parents, Keith and Rhetta Wheeler, serve as missionaries among the Native Americans in Montana; after graduating a year early from high school, Josiah was preparing to serve among the Inuit people groups in Northern Alaska.

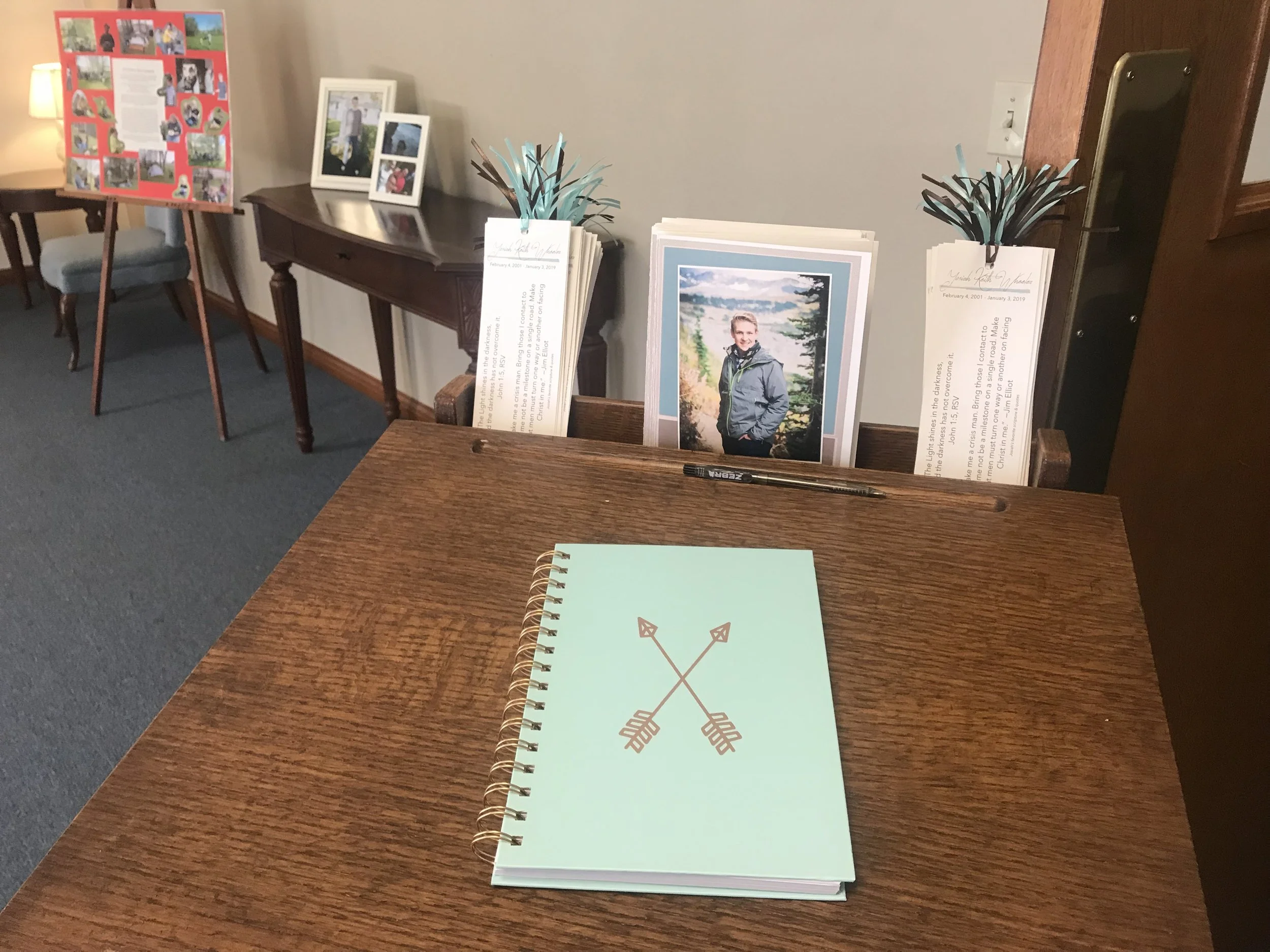

I grew up next-door to Josiah; we were born in houses that stand side-by-side. I was his babysitter (which he loathed) and Sunday School teacher. As we matured and grew up he became a close friend to me. It was my privilege to compile a video of pictures and memories for the services to honor his life — held in Alaska, Montana, South Dakota, and Indiana. I planned and coordinated his Indiana service which took place last Saturday, scrawling the majority of this reflection in the middle of the night preceding the service. The ending paragraphs I also read at both his Montana and South Dakota funerals before I sang.

This is only a smattering of stories and memories from the places where our stories intersected. A history cannot be told in a day; a lifetime cannot be condensed to a moment.

These are lines which none of us practiced to recite. Regardless of the role we each played in Josiah’s life, this was not a part we thought we’d play. We could not have imagined that we would help to tell his story like this. And everything feels quite unfinished. We thought the ending would be different.

I look back at the scenes and acts in which I took part alongside him, and the scenes move slowly, as if recorded in slo-mo, and frames freeze, and I catch my breath. And I stare at the script that is now mine to follow, try to reconcile the part I played before and during Josiah and the part I am to play now, in the after. And I realize that a chasm, an uncrossable crevice, has cut right through the heart of things, right through to where things matter most. And I must try to reach back to the life that once was, sort and sift through the pieces that he left us, and find the lessons I must remember for the story that is yet to be written.

Many of the lessons I must remember were not so much things he taught me, as much as they were things he helped me to appreciate more deeply or lessons we learned side-by-side.

Things like words. Words like chutzpah, temerity, multifarious, prolix, discursive, ostensibly, and ergonomics, to name a few that were a part of our casual conversations. When the Wheelers came home for a visit one summer when Josiah was 14, I took Josiah, Charity, and my little sister Mercy school supply shopping (as was a yearly tradition for the three of them). And it seemed that every single item he considered for purchase, he would discuss the ergonomics of its engineering and structure: the pencils, the notebooks, the erasers. I mean, I understand the importance of comfort and efficiency, but I thought he was applying the word with a little too much liberality. As we both got older, it became one of my greatest pleasures to “casually” use a word to which he didn’t know the meaning. And it became his delight to catch me questioning the usage of a word. With every new word I learn (almost on a daily basis), I remember him, and the pleasure he took in beautiful language.

Another thing that Josiah helped me to appreciate more deeply was art. Though, as you can see from his drawings that he was a gifted artist, I’m not referring to art of this kind. I’m referring to the art of stringing words together, end-to-end, like this. Like a picture in a sentence or a story in a song. That was something I shared with him like I share with few other people. He could appreciate arranging words in funny or serious or thought-provoking ways. And funny he was. Once I was trying to describe some friends of mine to him. I explained, “I think they’re more laid back than me.” He didn’t find this qualifier helpful. “Merilee,” he retorted, “I’m pretty sure the world is more laid back than you.” It became our custom to share original lyrics or poetry that we were writing and give each other feedback. He was the first person to hear some of my songs. He sent me his song, “Carry Me, Jesus” during his senior year of high school and one part I critiqued in the song was the line, “Carry me home, Lord/ Carry me there” because, as I told him, I didn’t see him at the Jordan River ready to cross over. And our last conversation, the week before Jesus carried him home, was a discussion about whether or not syllables should be counted and measured in poetry.

Maybe the most powerful lesson I learned alongside Josiah, as we both practiced parts we thought we’d be playing for years to come, is that relationships matter most. Josiah was willing to invest a lot of time and energy into the relationships and friendships with which his life was surrounded. This was evident from a young age. While he was still living next-door our youth group would go out every Thursday night to minister at a mission church in Kokomo. I can still see him, sitting in the semi-darkness toward the front of the 15-passenger van. The attention of all the teens was directed to the contest that was taking place on the front bench: 12- or 13-year-old Josiah against a 30-some-year-old passenger who was just along for the ride. They were each chewing and swallowing an entire banana peel as quickly as possible so as to beat their opponent. At the time, I just thought Josiah liked to try disgusting entrees. He told us much later that he was only engaging in such a race to help the 30-some-year-old man feel a part. Relationships mattered to him, and that was evident in everything he did.

Another lesson that Josiah knew well was the importance of his family, both immediate and extended. He always had a deep love and respect for Charity that was evidenced in so many ways, even if his mom had to limit the times he was permitted to torment or scare her to once per day. He especially appreciated her domestic skills. On one occasion, while they lived next-door to us, Charity had broken curfew (a cardinal sin in the Wheeler household) by mere minutes. As she came strolling up the sidewalk to their house she was greeted by her brother, dancing on the front porch as he exclaimed, “I don’t have to do dishes for a week! I don’t have to do dishes for a week!” Yes, he loved his family, but that night he especially loved Charity.

Finally, and perhaps the lesson that I’ll always be learning and relearning, the lesson that Josiah and I delved into the most deeply, is what God looks like and how He acts. This was the object of many hours of discussion between the two of us. Although we both took somewhat unorthodox views on the subject, we didn’t always agree. Last November, again we talked about the goodness of God and what that looks like.

I want to share what he wrote me for three reasons: 1) I feel it gives a really good overarching picture of the way he viewed his own story and the part he played; 2) I think that for those of us gathered here, his untimely death would seem to demand an explanation from a God Who is all-knowing and all-loving; and 3) that for moving forward from this day, we should understand God’s goodness the way Josiah saw it just seven weeks to the day before he passed away.

And here I quote Josiah (very slightly edited):

“I’ve come to the conclusion that, 1. many of the Scriptures we use as “promises” to oblige God to behave a certain way have been taken out of context, and 2. I don’t know what’s best for me in the first place. When I [went through a certain very difficult experience], I did not view my situation as remotely good. In hindsight, I wouldn’t trade that experience for the world. God, in His omniscient foresight, saw what this proud boy needed. And in His Goodness, He crushed me. I thanked Him for it this very morning in my devotions. There are things I still don’t understand, maybe never will. Perhaps when I get to Heaven and ask my Father, He will simply respond, as He did to a far greater questioner, ‘What is that to thee? Follow thou me.’ Perhaps those trials were to make me weaker, so that His strength would be my sustenance. Perhaps those trials were to make me look to Him for approval... Perhaps those trials were to humble an arrogant spirit. God only knows. And that’s okay, because He knows best.”

And so we choose to play our parts well, to follow these scripts that don’t make sense and trust that the Great Author of this Play is writing a plot that is beyond our comprehension and understanding.

And He knows best.